Licht als Welle

Modell mit λ und ν

© 2016

- 2025

Basiswissen|

Wie entstand die Idee von Licht als einer Welle?|

Licht als reine Welle|

Licht als Welle und Teilchen|

Das Superpositionsargument|

Die Lichtwelle spürt keine Gravitationskraft|

Was ist eine Abduktion?|

Fußnoten

Basiswissen

λ ist die Wellenlänge und ν (griechisches ny) eine Frequenz. Lichtphänomene werden oft mit λ und ν berechnet. Die Idee dahinter ist, dass Licht Eigenschaften ähnlich einer Wasserwelle hat. Man kann dabei Licht als reine Welle betrachtet oder als einen Teilchenstrom mit wellenartigen Eigenschaften. Beide Varianten werden hier kurz vorgestellt.

Wie entstand die Idee von Licht als einer Welle?

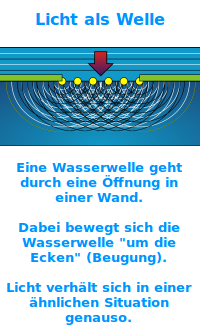

Im 17ten Jahrhundert hatte man beobachtet, dass Leuchteffekte an Stellen auftreten, an denen eigentlich streng geometrisch gedacht absolut dunkler Schatten sein müsste. Licht schien sich irgendwie um Objekte herumbewegen zu können. Der italienische Physiker Francesco Maria Grimaldi bemerkte, dass Wellen, etwa an Bunen oder dicken Felsen im Wasser, genau auch dieses Verhalten zeigen: sie wandern um das Hindernis herum. Grimaldi folgerte daraus, dass vielleicht auch Licht etwas Wellenhaftes an sich haben könnte[1]. Mehr unter Francesco Maria Grimaldi ↗

Licht als reine Welle

Wenn Licht an einer scharfen Kante vorbeigeführt wird, dann beugt es sich um diese Kante herum. Reine Kügelchen (Licht als Teilchen) würden sich nie so verhalten. Wasserwellen aber würden genau dieses Verhalten produzieren. Solche und andere[6][7] Beobachtungen veranlassten den Niederlände Christiaan Huygens zu der Idee, Licht sei ein Wellenphänomen. Damit ließen sich qualitativ Phänomene wie Beugung, Brechung und Interferenz[10] sehr gut erklären. Mehr dazu unter Huygenssches Prinzip ↗

Licht als Welle und Teilchen

Man kann Licht bewusst im sogenannten Wellen-Teilchen-Dualismus betrachten. In dem Modell besteht es einerseits aus eng umgrenzten Teilchen. Welche Form der Bewegung das Teilchen dabei vollzieht ist weitgehend offen.[11] Andererseits aber verwendet man Formeln mit Wellenlängen lambda und Frequenzen f oder ny, also Vorstellungen, die nur auf Wellen passen. Dieser Ansatz ist in der Physik sehr erfolgreich, aber nicht unumstritten[3][4]. Mehr zu dieser dualistischen Sichtweise steht unter Photonenwelle ↗

Das Superpositionsargument

Der Niederländer Christiann Huygens (1629 bis 1965) ging davon aus, dass letztendlich auch Licht mechanisch erklärbar sein muss[5]. Mechanisch heißt, dass es eine materielle Grundlage geben muss. Umherfliegende Teilchen können aber ausgeschlossen werden, so Huygens, da sich kreuzende Lichtstrahlen sich gegenseitig nicht stören[6]. Als Lösung bietet sich die Analogie zum Schall an, wo Huygens (korrekterweise) eine Ausbreitung von Schwingungen annimmt[7]. Huygens beschreibt Licht als wellenartig und nennt ausdrücklich die Welle auf einer Wasseroberfläche als Analogie[9]. Siehe auch Superposition ↗

Die Lichtwelle spürt keine Gravitationskraft

Der Astrophysiker Arthur Stanley Eddington (1882 bis 1944) hatte die Ablenkung von Lichtstrahlen im Sinne der Einsteinschen Relativitätstheorie mit astronomischen Beobachtungen bestätigt. Doch im reinen Wellenmodell des Lichts dürfte keine Licht keine gravitative Kraft spüren:

Es war eine der großen Stärken Eddingtons, dass er in seinen Erklärungen solange wie möglich bei allgemein verständlichen Denkbildern blieb, für die jeder bemühte Denker eine Chance hat, sie nachzuvollziehen. Wenn aber Licht beim Passieren der Sonne tatsächlich abgelenkt wird, was ist dann die Ursache? Die Antwort, so Eddington (und nicht nur er) lag in der einsteinschen Idee einer gekrümmten Raumzeit ↗

Was ist eine Abduktion?

Das ist eine Denkfigur, die oft in den Naturwissenschaften angewandt wird, meist unbewusst und intuitiv. Bis etwa 1650 ging man davon aus, dass sich Licht strahlenartig und geradlinig ausbreitet. Wenn man nun beobachtet, dass Licht sich um eine Kante herumbiegen kann (Effekt der Beugung) wäre das unter der Annahme von Strahlen überraschend. Wer aber auf diese Beobachtung hin auf die Idee kommt, dass Licht vielleicht wellenartig ist, hätte die Überraschung zu einer Selbstverständlichkeit gemacht: Wellen wandern um Hindernisse herum (z. B. Wasserwellen an Buhnen). Lies mehr zu dieser Denkfigur unter Abduktion ↗

Fußnoten

- [1] Die früheste oder einer der frühesten Äußerungen über die Wellennatur des Lichts schreibt man dem Italiener Francesco Maria Grimaldi zu: "light seem[ed] to be some very fast fluid, sometimes also undulating..." und "The modification of light through which it is colored ... can probably be said to be determined by its exceedingly fine undulation [ipsius undulatione minutissime crispata], as in some trembling flow [tremor diffusionis], with the most subtle rolling [certa fluitatione subtilissima] through which it affects the sense of vision by proper and determined application." Die Originalworte Grimaldis stammen aus seinem Buch "De Lumine" und wurden später in Englische übersetzt. In: Oliver Darrigol: A History of Optics. From Greek Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. 2012. ISBN: 978–0–19–964437–7. Dort die Seiten 58 und 59. Siehe auch De Lumine, coloribus, et iride ↗

- [2] Newton (1627 bis 1727) erwog Licht auch als Wellenphänomen: "If a stone be thrown into stagnating Water, the Waves excited thereby continue some time to arise in the place where the Stone fell into the Water, and are propagated from thence in concentrick Circles upon the Surface of the Water to great distances. And the Vibrations or Tremors excited in the Air by percussion, continue a little time to move from the place of percussion in concentrick Spheres to great distances. And in like manner, when a Ray of Light falls upon the Surface of any pellucid Body, and is there refracted or reflected, may not Waves of Vibrations, or Tremors, be thereby excited in the refracting or reflecting Medium at the point of Incidence, and continue to arise there, and to be propagated from thence as long as they continue to arise and be propagated, when they are excited in the bottom of the Eye by the Pressure or Motion of the Finger, or by the Light which comes from the Coal of Fire in the Experiments above-mention'd? and are not these Vibrations propagated from the point of Incidence to great distances? And do they not overtake the Rays of Light, and by overtaking them successively, do they not put them into the Fits of easy Reflexion and easy Transmission described above? For if the Rays endeavour to recede from the densest part of the Vibration, they may be alternately accelerated and retarded by the Vibrations overtaking them." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The_ FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730).

- [3] Der Physiker und Nobelpreisträger Richard Feynman (1918 bis 1988) betonte immer wieder, dass Licht keine Welle sondern ein Teilchen sei: "Ich betone noch einmal, daß Licht in dieser Form - als Teilchen - auftritt. Es verhält sich genauso, wie sich Teilchen verhalten. Das müssen sich vornehmlich diejenigen unter Ihnen einprägen, die in der Schule vermutlich etwas vom Wellencharakter des Lichts erzählt bekamen. In Wirklichkeit aber ist das Verhalten des Lichts das von Teilchen." Sowie: "Viele Jahre nach Newton wurde mit der Wellentheorie eine vollauf befriedigende Erklärung für die partielle Reflexion des Lichts an zwei Grenzflächen gefunden, aber als man Experimente mit sehr schwachem Licht durchführte und es durch Photoelektronen-Vervielfacher schickte, brach die Wellentheorie in sich zusammen. In: Richard Feynman: QED: Die seltsame Theorie des Lichts und der Materie. Piper Verlag. 1. Auflage 1992. ISBN: 3-492-21562-9. Dort die Seite 26 sowie 34 und 35. Feynman entwickelte einen mathematischen Formalismus, seine Quantenelektrodynamik mit den sogenannten Quantenpfaden. Dieser Formalismus kommt zu exakt denselben Ergebnissen wie die Wellenoptik, ohne jedoch irgendwo in Wellen zu denken. Siehe auch QED (Feynman) ↗

- [4] Der Physiker Richard Feynman (1918 bis 1988) hielt die Wellentheorie des Lichts für falsch: "Viele Jahre nach Newton wurde mit der Wellentheorie eine vollauf befriedigende Erklärung für die partielle Reflexion des Lichts an zwei Grenzflächen gefunden, aber als man Experimente mit sehr schwachem Licht durchführte und es durch Photoelektronen-Vervielfacher schickte, brach die Wellentheorie in sich zusammen: Obwohl das Licht immer schwächer wurde, ertönten die Klicks des Photo-Multipliers weiterhin in voller Stärke - nur weniger oft. Das Licht verhielt sich wie ein Teilchen." Quelle: Richard Feynman: QED: Die seltsame Theorie des Lichts und der Materie. Piper Verlag. 1. Auflage 1992. ISBN: 3-492-21562-9. Siehe auch QED (Feynman) ↗

- [5] Huygens nimmt eine materielle, mechanische Grundlage von Licht an: "It is inconceivable to doubt that light consists in the motion of some sort of matter. For whether one considers its production, one sees that here upon the Earth it is chiefly engendered by fire and flame which contain without doubt bodies that are in rapid motion, since they dissolve and melt many other bodies, even the most solid; or whether one considers its effects, one sees that when light is collected, as by concave mirrors, it has the property of burning as a fire does, that is to say it disunites the particles of bodies. This is assuredly the mark of motion, at least in the true Philosophy, in which one conceives the causes of all natural effects in terms of mechanical motions. This, in my opinion, we must necessarily do, or else renounce all hopes of ever comprehending anything in Physics." In: Treatise on light In which are explained the causes of that which occurs in reflexion, & in refraction and particularly in the strange refraction of Iceland crystal. Aus dem Französischen übersetzt von Silvanus P. Thompson. Französisches Original aus dem Jahr 1690: Traite de la Lumiere. Dort die Seite 3.

- [6] Huygens schließt umherfliegende Teilchen des Lichts aus, das sich Licht aus verschiedenen Richtungen selbst bei einer Überkreuzung nicht gegenseitig stört: "Further, when one considers the extreme speed with which light spreads on every side, and how, when it comes from different regions, even from those directly opposite, the rays traverse one another without hindrance, one may well understand that when we see a luminous object, it cannot be by any transport of matter coming to us from this object, in the way in which a shot or an arrow traverses the air; for assuredly that would too greatly impugn these two properties of light, especially the second of them. It is then in some other way that light spreads; and that which can lead us to comprehend it is the knowledge which we have of the spreading of Sound in the air." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 4. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690. Dort die Seiten 3 und 4.

- [7] Huygens sieht Licht in Analogie zum Schall in Luft: "We know that by means of the air, which is an invisible and impalpable body, Sound spreads around the spot where it has been produced, by a movement which is passed on successively from one part of the air to another; and that the spreading of this movement, taking place equally rapidly on all sides, ought to form spherical surfaces ever enlarging and which strike our ears. Now there is no doubt at all that light also comes from the luminous body to our eyes by some movement impressed on the matter which is between the two; since, as we have already seen, it cannot be by the transport of a body which passes from one to the other." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 4. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [8] Die Lichtbewegung muss das Auge erreichen: "And as, according to this Philosophy, one holds as certain that the sensation of sight is excited only by the impression of some movement of a kind of matter which acts on the nerves at the back of our eyes, there is here yet one reason more for believing that light consists in a movement of the matter which exists between us and the luminous body." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 3. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [9] Das Licht breitet sich als Welle aus: "We know that by means of the air, which is an invisible and impalpable body, Sound spreads around the spot where it has been produced, by a movement which is passed on successively from one part of the air to another; and that the spreading of this movement, taking place equally rapidly on all sides, ought to form spherical surfaces ever enlarging and which strike our ears. Now there is no doubt at all that light also comes from the luminous body to our eyes by some movement impressed on the matter which is between the two; since, as we have already seen, it cannot be by the transport of a body which passes from one to the other. If, in addition, light takes time for its passage—which we are now going to examine—it will follow that this movement, impressed on the intervening matter, is successive; and consequently it spreads, as Sound does, by spherical surfaces and waves: for I call them waves from their resemblance to those which are seen to be formed in water when a stone is thrown into it, and which present a successive spreading as circles, though these arise from another cause, and are only in a flat surface." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 4. Im Französischen Original spricht er von "onde", also Welle. In: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [10] Das Licht keine "Substanz", das heißt keine stoffliche Materie ist, schlussfolgerte im Jahr 1878 der Physiker James Clerk Maxwell Schritt für Schritt aus dem Phänomen der Interferenz: "That light is not itself a substance may be proved from the phenomenon of interference. A beam of light from a single source is divided by certain optical methods into two parts, and these, after travelling by different paths, are made to reunite and fall upon a screen. If either half of the beam is stopped, the other falls on the screen and illuminates it, but if both are allowed to pass, the screen in certain places becomes dark, and thus shows that the two portions of light have destroyed each other. Now, we cannot suppose that two bodies when put together can annihilate each other; therefore light cannot be a substance. What we have proved is that one portion of light can be the exact opposite of another portion, just as +a is the exact opposite of -a, whatever a may be. Among physical quantities we find some which are capable of having their signs reversed, and others which are not. Thus a displacement in one direction is the exact opposite of an equal displacement in the opposite direction. Such quantities are the measures, not of substances, but always of processes taking place in a substance. We therefore conclude that light is not a substance but a process going on in a substance, the process going on in the first portion of light being always the exact opposite of the process going on in the other at the same instant, so that when the two portions are combined no process goes on at all." In: James Clerk Maxwell: "Ether", Encyclopædia Britannica Ninth Edition, 8: 568 - 572. 1878. Online: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Encyclopædia_Britannica,_Ninth_Edition/Ether_(2.)

- [11] James Clerk Maxwell lässt offen, was bei einem Lichtteilchen auf seinem Weg durch den Raum schwingt. Zur Erklärung konstruktiver und vor allem destruktiver Interferenz genügt es, wenn man irgendeinen nicht näher bestimmten Prozess annimmt, bei dem physikalische Größen sowohl positive wie auch negative Werte annehmen können. So kann es durch Addition einer Zahl und ihrer Gegenzahl zur Summe 0 und damit zu destruktiver Interferenz kommen: "It may be a displacement, or a rotation, or an electrical disturbance, or indeed any physical quantity which is capable of assuming negative as well as positive values. Whatever be the nature of the process, if it is capable of being expressed by an equation of this form, the process going on at a fixed point is called a vibration". In: James Clerk Maxwell: "Ether", Encyclopædia Britannica Ninth Edition, 8: 568 - 572. 1878. Online: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Encyclopædia_Britannica,_Ninth_Edition/Ether_(2.)

- [12] Warum Lichtwellen keine Gravitationskraft spüren sollten: "Light-waves in passing a massive body such as the sun are deflected through a small angle. This is additional evidence that the Newtonian picture of gravitation as a tug is inadequate. You cannot deflect waves by tugging at them, and clearly another representation of the agency which deflects them must be found." In: Arthur Stanley Eddington: The Nature of the Physical World. MacMillan, 1928 (Gifford Lectures). Dort im Kapitel "Gravitation". Seite 122.