Huygenssches Prinzip

Optik

© 2016

- 2025

Basiswissen|

Was sollte das Modell erklären?|

Was musste Huygens annehmen, ohne es erklären zu können?|

Was stand im Widerspruch dazu?|

Gibt es eine übergeordnete Theorie?|

Fußnoten

Basiswissen

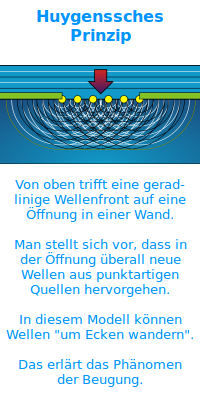

Kugelwellenmodell für Beugung, Brechung und Reflexion von Wellen: Das Konzept wurde im Jahr 1678 von Christiaan Huygens vorgeschlagen, um die Ausbreitung von Licht zu erklären. Demnach ist jeder Punkt, der von einer Wellenfront erreicht wird, Ausgangspunkt für eine kugel- bzw. kreisförmige Elementarwelle, welche sich im selben Ausbreitungsmedium mit gleicher Geschwindigkeit ausbreitet wie die ursprüngliche Welle . Die sich weiter ausbreitende Wellenfront ergibt sich als äußere Einhüllende der Elementarwellen.

Was sollte das Modell erklären?

Huygens beobachtete wie Licht beim Übergang von Luft in Wasser seine Richtung ändert (Brechung). Er beobachtet auch, wie sich Licht um Ecken herum bewegt (Beugung). Beide Beobachtungen ließen sich nicht mit Hilfe von geradlinig im Raum sich ausbreitenden Teilchen erklären. Sie passten aber sehr gut auf die Idee, dass sich Licht wellenartig ausbreitet. Ein elementares Denkbild ist dabei die Elementarwelle. Huygens Prinzip lieferte eine qualitative Erklärung für die Beugung und Brechung.

Was musste Huygens annehmen, ohne es erklären zu können?

- Die neu entstandenen Elementarwellen bewegen sich nie rückwärts.

- Die Elemtarwellen breiten sich nimmer nur in eine Richtung aus.

- Huygens musste diesen Umstand annehmen, konnte ihn aber nicht erklären.

Was stand im Widerspruch dazu?

Man kann beobachten, dass sich Licht auch in Strahlen ausbreitet. Man kann mit Lampen zum Beispiel eng gefasste Strahlen erzeugen, die in den Himmel leuchtend weit sichbar sind. Reine Wellen aber breiten sich nicht strahlenartig aus.

Gibt es eine übergeordnete Theorie?

Sowohl der Wellen- als auch der Teilchencharakter von Licht werden in einer gemeinsamen Vorstellung zusammengefasst. Man kann damit alle Phänomene berechnen, verzichtet aber auf die Frage, woraus denn Licht genau besteht. Mehr dazu unter 👉 Welle-Teilchen-Dualismus

Fußnoten

- [1] Christiaan Huygens: Traite de la Lumiere | Ou sont Expliquees les causes de ce qui luy arrive dans la Reflexion, & dans la Refraction. Et particulierement dans l'etrange Refraction du Cristal d'Islande. Veröffentlicht in Leiden im Jahr 1690. Deutsch: Abhandlung über Reflexion und Refraktion, Wellentheorie des Lichts. Worin die Ursachen der Vorgänge bei seiner Zurückwerfung und Brechung und besonders bei der eigenthümlichen Brechung des isländischen Spathes dargelegt sind. Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann, Leipzig 1890. Online: http://www.archive.org/details/abhandlungberda00mewegoog

- [2] "Every particle of the matter in which the wave spreads out communicates its motion not only to the next particle that is on the straight line drawn from the luminous point, but it also gives some motion to all other particles that touch it and that oppose its motion." In: 1690 Traite´ de la lumiere ou` sont expose´es les causes de ce qui lui arrive dans la re´flexion, et dans la re´fraction, et particulierement dans l’e´trange re´fraction du cristal d’Islande. Avec un discours de la cause de la pesanteur. Leiden: van der Aa. Dort die Seite 17. Übersetzt in Oliver Darrigol: A History of Optics. From Greek Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. 2012. ISBN: 978–0–19–964437–7. Dort die Seite 69.

- [3] Rowan Hamilton schreibt 1833 über Huygens Idee von Licht in einem Äther: "Huygens, who compared the gradual propagation of light, not to the

to our ears; but only the aerial motion spreads, the air near the cannon is disturbed first, then that which is a little farther, and last of all the air that touches us. Or like the waves that spread and grow upon some peaceful lake, when a pebble has stirred its surface; the floating water-lilies rise and fall, but scarcely quit their place, while the enlarging wave passes on and moves them in succession. So that great ocean of ether which bathes the farthest

stars, is ever newly stirred, by waves that spread and grow, from every source of light, till they move and agitate the whole with their minute vibrations: yet like sounds through air, or waves on water, these multitudinous disturbances make no confusion, but freely mix and cross, while each retains its identity, and keeps the impress of its proper origin. Such is the view of Light which Huygens adopted, and which justly bears his name; because, whatever

kindred thoughts occurred to others before, he first shewed clearly how this view conducted to the laws of optics, by combining it with that essential principle of the undulatory theory which was first discovered by himself, the principle of accumulated disturbance. According to this principle, the minute vibrations of the elastic luminous ether cannot perceptibly affect our eyes, cannot produce any sensible light, unless they combine and concur

in a great and, as it were, infinite multitude; and on the other hand, such combination is possible, because particular or secondary waves are supposed in this theory to spread from every vibrating particle, as from a separate centre, with a rapidity of propagation determined by the nature of the medium. And hence it comes, thought Huygens, that light in any one uniform medium diffuses itself only in straight lines, so as only to reach those parts of space to which a straight path lies open from its origin; because an opaque obstacle, obstructing such straight progress, though it does not hinder the spreading of weak particular waves into the space behind it, yet prevents their accumulation within that space into one grand general wave, of strength enough to generate light. This want of accumulation of separate vibrations behind an obstacle, was elegantly proved by Huygens: the mutual destruction of such vibrations by interference, is an important addition to the theory, which has been made by Young and by Fresnel. Analogous explanations have been offered for the laws of reflexion and refraction." In: Hamilton, William Rowan, Sir (1833). On a general method of expressing the paths of light, & of the planets, by the coefficients of a characteristic function. Printed by P.D. Hardy.