Satz vom ausgeschlossenen Dritten

Ein Axiom der Logik

© 2016

- 2025

Basiswissen|

Die Endlichkeit der Welt als Beispiel|

Schreibweise|

Tertium non datur|

Gilt dieser Satz z. B. in der Physik?|

Originalzitat von Aristoteles|

Fußnoten

Basiswissen

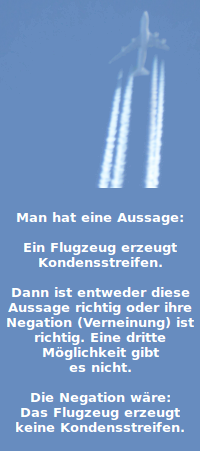

Ein Axiom ist ein bewusst gesetzte Grundannahme die man ab dann nicht mehr hinterfragen möchte. Dass eine Aussage entweder wahr ist oder aber - falls sie nicht wahr ist - automatisch ihre Verneinung gilt, ist ein Axiom der Logik.

Die Endlichkeit der Welt als Beispiel

Die Welt, das Universum in dem wir leben ist entweder endlich oder es ist unendlich. Eine dritte Möglichkeit gibt es nicht: tertium non datur.[3]

Schreibweise

- P v ¬P

- P steht für eine beliebige Aussage (Proposition).

- Ein Beispiel für ein P wäre:

- v ist ein logisches Oder ↗

- ¬ ist die Negation, gelesen: nicht

- Also: Es ist P oder es ist nicht-P (die Verneinung)

- Siehe auch unter ¬ ↗

Tertium non datur

- In der Literatur wird oft diese lateinische Kurzform zitiert.

- Sie heißt auf deutsch: Ein Drittes gibt es nicht.

- Lies auch unter Tertium non datur ↗

Gilt dieser Satz z. B. in der Physik?

- Das ist nicht sicher.

- Es gibt begründete Anlässe für Zweifel, z. B. das ...

- sogenannte Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Paradoxon:

- Wenn ein Teilchen durchgängig und lückenlos durch die Zeit existiert ...

- und wenn es gleichzeitig einen immer exakten Aufenthaltsort hat ...

- und wenn es nicht ohne Zwischenstufen zwischen Orten springen kann, ...

- dann ist möglicherweise der Satz vom ausgeschlossenen Dritten verletzt.

- Siehe mehr dazu unter Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Paradoxon ↗

Originalzitat von Aristoteles

„Daß nämlichdasselbe demselben in derselben Beziehung unmöglich zugleich zukommen und nicht zukommen kann, das ist das sicherste unter allen Prinzipien, denn es paßt darauf die angegebene Bestimmung, da es unmöglich ist, daß jemand annehme, dasselbe sei und sei nicht.“[1]

Fußnoten

- [1] Aristoteles, Metaphysik, 1005b19-24 (deutsche Übersetzung von H. Bonitz, Hamburg 1978.

- [2] Der Physiker Franz Serafin Exner formulierte ein klassisches Problem der Art tertium non datur am Beispiel der Entstehung von Materie: "Es ist uns ebenso unbegreiflich, zu denken, daß die Materie von jeher existiert, wie dass sie einmal aus Nichts entstanden ist. Und doch scheint ein Drittes nicht möglich." In: Franz Serafin Exner: Vorlesungen über die physikalischen Grundlagen der Naturwissenschaften. Deuticke, Wien 1919, OBV. Dort die "63. Vorlesung". Seite 472. Siehe auch ex nihilo nihil fit ↗

- [3] Dass dennoch beide Möglichkeiten gleichzeitig wahr sein könnten erläutert Albert Einstein in: Über die spezielle und die allgemeine Relativitätstheorie. WTB Wisschenschaftliche Taschenbücher. Akademie Verlag. Berlin (DDR). 1979. Erstveröffentlichung im Jahr 1916. Dort im "§ 31. Die Möglichkeit einer endlichen und doch nicht begrenzten Welt." Siehe auch Unendlichkeitsdilemma ↗

- [4] Der US-amerikanische Dichter und Schriftsteller Edgar Allan Poe (1809 bis 1849) thematisiert in seiner satirischen Kurzgeschichte "Eureka" die Frage, ob die menschliche Unfähigkeit, sich etwas gedanklich vorstellen zu können gleichzeitig auch ein Kriterium für objekte Wahrheit sein kann. Er tut dies am Beispiel des Satzes von ausgeschlossenen Dritten: Kann etwas ein Baum und gleichzeitig kein Baum sein? Im Original: "We will select for investigation no common-place axiom — no axiom of what, not the less preposterously because only impliedly, he terms his secondary class — as if a positive truth by definition could be either more or less positively a truth: — we will select, I say, no axiom of an unquestionability so questionable as is to be found in Euclid. We will not talk, for example, about such propositions as that two straight lines cannot enclose a space, or that the whole is greater than any one of its parts. We will afford the logician every advantage. We will come at once to a proposition which he regards as the acme of the unquestionable — as the quintessence of axiomatic undeniability. Here it is: — ‘Contradictions cannot both be true — that is, cannot cöexist in nature.’ Here Mr. Mill means, for instance, — and I give the most forcible instance conceivable — that a tree must be either a tree or not a tree — that it cannot be at the same time a tree and not a tree: — all which is quite reasonable of itself and will answer remarkably well as an axiom, until we bring it into collation with an axiom insisted upon a few pages before — in other words — words which I have previously employed — until we test it by the logic of its own propounder. ‘A tree,’ Mr. Mill asserts, ‘must be either a tree or not a tree.’ Very well: — and now let me ask him, why. To this little query there is but one response: — I defy any man living to invent a second. The sole answer is this: — ‘Because we find it impossible to conceive that a tree can be any thing else than a tree or not a tree.’ This, I repeat, is Mr. Mill's sole answer: — he will not pretend to suggest another: — and yet, by his own showing, his answer is clearly no answer at all; for has he not already required us to admit, as an axiom, that ability or inability to conceive is in no case to be taken as a criterion of axiomatic truth? Thus all — absolutely all his argumentation is at sea without a rudder. Let it not be urged that an exception from the general rule is to be made, in cases where the ‘impossibility to conceive’ is so peculiarly great as when we are called upon to conceive a tree both a tree and not a tree. Let no attempt, I say, be made at urging this sotticism; for, in the first place, there are no degrees of ‘impossibility,’ and thus no one impossible conception can be more peculiarly impossible than another impossible conception: — in the second place, Mr. Mill himself, no doubt after thorough deliberation, has most distinctly, and most rationally, excluded all opportunity for exception, by the emphasis of his proposition, that, in no case, is ability or inability to conceive, to be taken as a criterion of axiomatic truth: — in the third place, even were exceptions admissible at all, it remains to be shown how any exception is admissible here. That a tree can be both a tree and not a tree, is an idea which the angels, or the devils, may entertain, and which no doubt many an earthly Bedlamite, or Transcendentalist, does." In: In: Edgar Allan Poe: Eureka: An Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe. 1848. Übersetzt ins Deutsche von: Heinz Janisch als Eureka. Ein Prosagedicht. Insel Verlag 1994. Siehe auch Axiom ↗