Lichtäther

Begründung

© 2016

- 2026

Basiswissen|

Geschichte der Äther-Idee|

Gründe für die Existenz einer Äthers|

Oszillatoren als mechanische Voraussetzung|

Der Äther liefert die Oszillatoren|

Der Äther erklärt Rotverschiebung über Doppler-Effekt|

Frühe Probleme mit dem Äther-Bild|

Eigenschaften des Äthers|

Der Ätherwind|

Ätherwellen sind transversal|

Die Äthermitführung|

"Wasser-Äther" als anschauliches Modell|

Experimentum crucis: Michelson-Morley|

Alber Einstein zum Äther|

Arnold Sommerfeld zum Äther|

Eine fixe Idee?|

Fußnoten

Basiswissen

Die Ausbreitung von Licht lässt sich mit Formeln beschreiben, die man auch auf Wellen anwenden kann. Wenn aber Licht wellenartig ist, was spielt dann die Rolle des Wassers im Vakuum des Weltraums? Diese Frage reicht zurück bis ins 17te Jahrhundert [15] und führte zu einer Vielzahl konkreter Annahmen über die Natur des Äthers. [25] Die bisher erfolglose Suche nach dem Äther führte 1905 zur Entstehung von Einsteins Relativitätstheorie.

Geschichte der Äther-Idee

- Dass Licht etwas Wellenartiges sein könnte formulierte schon sehr früh 👉 Francesco Maria Grimaldi

- Eine ausdrückliche Wellentheorie des Lichts erstellte dann im 17ten Jahrhundert der Physiker 👉 Christiaan Huygens

- Dieser, so konnte man zeigen, war nicht der Stoff in dem sich Schall ausbreitete. [11]

- Um eine Fernwirkung, etwa auch seiner Gravitationskraft zu vermeiden, nahm auch Newton einen Äther an. [28]

- Im frühen 19ten Jahrhundert hatte sich diese Wellenidee des Lichts weitgehend durchgesetzt. [16] [22] [24]

- Ein Äther wurde dabei als selbstverständlich [27] oder zumindest mechanistisch plausibel [43] angenommen.

- Siehe zum Beispiel 👉 Doppelspaltexperiment nach Young

Gründe für die Existenz einer Äthers

- Wellen "bestehen" aus Schwingungen, Schwingungen benötigen einen 👉 Oszillator

- Licht kann Druck ausüben und Impuls übertragen Lichtdruck👉 [29]

- Mögliche Erklärung der astronomischen Rotverschiebung👉 [30]

- Der Effekt der Aberration [4] [31]👉 [37]

Oszillatoren als mechanische Voraussetzung

- Bei Wellen gibt es immer ein Medium, in dem sie sich ausbreiten [7].

- Klassisch gedachte Wellen brauchen immer schwingende Oszillatoren.

- Bei Wasserwellen sind es zum Beispiel die Wasserteilchen.

- Bei Schallwellen sind es die Luftmoleküle [9].

- Was schwingt bei Lichtwellen im Vakuum?

- Diese Frage führte zum Äthergedanken.

Der Äther liefert die Oszillatoren

- Man postulierte (nahm an), dass auch das Vakuum Oszillatoren hat.

- Diese Oszillatoren stellte man sich als feinste Teilchen vor.

- Die Gesamtheit dieser Teilchen nannte man den Lichtäther.

- Der Äther vermittelte elektrische und magnetische Schwingungen. [26]

- Siehe zum Beispeil 👉 Newtons Äther

Der Äther erklärt Rotverschiebung über Doppler-Effekt

Eine Konsequenz aus der Konstanz der Geschwindigkeit c von Wellen in ihrem Medium ist der sogenannte Doppler-Effekt. Um diesen Effekt zu verstehen, muss man noch die Bedeutung der Frequenz verstehen. Als Frequenz bezeichnet man die Anzahl der vollständigen Schwingungen die ein Messgerät oder Beobachter in einer bestimmten Zeiteinheit zählt. Bei Wasserwellen könnte man die Frequenz an einem bestimmten Ort, darüber messen, dass man einfach die Anzahl der Wellenberge zählt, die in einer bestimmten Zeitraum dort eintreffen. Die Anzahl der Wellenberge pro Zeiteinheit ist dann die Frequenz. Bewegt sich nun das Medium der Wellen relativ zum Beobachter oder der Beobachter relativ zum Medium, dann erhält man eine andere Frequenz, als bei einem zum Medium ruhenden Beobachter. Darüber ließe sich die Rotverschiedung weit entfernter Himmelskörper erklären. Siehe mehr dazu unter 👉 Doppler-Effekt

Frühe Probleme mit dem Äther-Bild

Man stellt sich den Äther vor, um etwas mehr oder minder Mechanisches zu haben, das die Schwingungen des Lichts überträgt. Dass diese Vorstellung aber zu Problemen führen kann, soll spätestens im Jahr 1843 offensichtlich geworden sein. Der Physiker und Nobelpreisträger Richard Feynman schrieb gut 120 Jahre später:

ZITAT:

"Die Versuche, das elektrische Feld als die Bewegung von einer Art von Getriebe oder als Feldlinien oder als Spannungen in irgendeinem Material dazurstellen, haben die Physiker mehr Mühe gekostet, als notwendig gewesen wäre, um die richtigen Antworten der Elektrodynamik zu finden. Es ist interessant, dass die genauen Geichungen für das Verhalten von Licht in Kristallen von McCullough im Jahre 1843 aufgestellt wurden. Man sagte damals zu ihm: 'Ja, aber es gibt kein wirkliches Material, dessen mechanische Eigenschaften diese Gleichungen erfüllen könnten, und da Licht ein Schwingungsvorgang ist und also in etwas schwingen muss, können wir nicht an diese Sache mit den abstrakten Gleichungen glauben." [23]

"Die Versuche, das elektrische Feld als die Bewegung von einer Art von Getriebe oder als Feldlinien oder als Spannungen in irgendeinem Material dazurstellen, haben die Physiker mehr Mühe gekostet, als notwendig gewesen wäre, um die richtigen Antworten der Elektrodynamik zu finden. Es ist interessant, dass die genauen Geichungen für das Verhalten von Licht in Kristallen von McCullough im Jahre 1843 aufgestellt wurden. Man sagte damals zu ihm: 'Ja, aber es gibt kein wirkliches Material, dessen mechanische Eigenschaften diese Gleichungen erfüllen könnten, und da Licht ein Schwingungsvorgang ist und also in etwas schwingen muss, können wir nicht an diese Sache mit den abstrakten Gleichungen glauben." [23]

Tatsächlich besteht das Problem auch heute noch weiter. Zwar lässt sich das Verhalten von Licht in Materie und im Vakuum mit Gleichungen berechnen, die auch für idealisierte Wellen gelten. Aber weder hat man einen echten Lichtäther als Stoff bisher nachweisen können, noch kann man sich etwas Materielles und Schwingendes ausdenken, das auf die Mathematik der nötigen Schwingungen passt.

Eigenschaften des Äthers

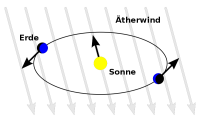

Der Ätherwind

Man nahm im 19ten Jahrhundert an, dass sich Licht und andere elektromagnetische Wellen mit einer konstanten Geschwindigkeit c durch den hypothetischen Äther bewegen. Eine Konsequenz aus dieser Konstanz der Geschwindigkeit c von Wellen in ihrem Medium ist der sogenannte Ätherwind. Ganz gleich, ob es gerade Wellen im Äther gibt oder nicht: bewegt sich ein Beobachter relativ zum Äther, so müsste der "Ätherstoff" dem Beobachter von einer Seite "ins Gesicht blasen". In der Analogie zu Wasserwellen wäre der Ätherwind die Anströmung die ein Beobachter in Richtung seiner Bewegung erfährt. Tatsächlich konnte ein Ätherwind für den hypothetischen Äther des Lichts niemals experimentell bestätigt werden. Im Gegenteil, das Michelson-Morley-Experiment widerlegte die Existenz eines Ätherwindes für die Wanderung der Erde durch den Weltraum. Siehe auch 👉 Ätherwind

Ätherwellen sind transversal

Im 19ten Jahrhundert entwickelte James Clerk Maxwell eine noch heute gültige Theorie des Elektromagnetismus. Auch Maxwell ging von der Existenz eines Äthers aus. Maxwells Äther war dabei nicht nur der Träger der Wellen des Lichts sondern auch der Wellen elektrischer und magnetischer Phänomene:

ZITAT:

"The velocity of transverse undulations in our hypothetical medium, calculated from the electromagnetic experiments of Kohlrausch and Weber, agrees so exactly with the velocity of light calculated from the optical experiments of M. Fizeau, that we can scarcely avoid the conclusion that light consists in the transverse undulations of the same medium which is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena." [19]

"The velocity of transverse undulations in our hypothetical medium, calculated from the electromagnetic experiments of Kohlrausch and Weber, agrees so exactly with the velocity of light calculated from the optical experiments of M. Fizeau, that we can scarcely avoid the conclusion that light consists in the transverse undulations of the same medium which is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena." [19]

Maxwell argumentiert, dass Licht aus Undulationen, das heißt Schwingungen besteht, und dass diese Schwingungen transversal sind. Das heißt, die Oszillatoren schwingen senkrecht zur Fortpflanzung des Lichts. Tatsächlich führte die Vorstellung rein transversaler Ätherwellen aber selbst wiederum zu Problemen, da andere Überlegungen zwingend dazu führten, dass die Ätherwellen auch eine longitudinale Komponente haben müssten. Siehe auch 👉 Undulationstheorie

Die Äthermitführung

Im 19ten Jahrhundert kam immer wieder auch die Frage auf, ob durch den Äther sich bewegende Materie den Äther mit sich reißen könne, der Äther also auch viskos, das heißt zähflüssig sein könne. Die Alternative - schwer vorstellbar -, dass der Äther völlig durchdringbar ist wurde aber auch mitgedacht. [45] Im Englischen sprach man von einem ether drag, auf Deutsch von einer 👉 Äthermitführung

"Wasser-Äther" als anschauliches Modell

- Aus diesem Modell konnte man Annahmen über die Lichtgeschwindigkeit ableiten.

- Dazu erst ein einfaches Gedankenbild mit einfachen Wasserwellen.

- Man stelle sich vor, man schwebe auf dem Bauch liegend knapp über einer ruhigen Wasseroberfläche.

- Von oben lässt man dann ein kleines Steinchen auf das Wasser fallen.

- Das Steinchen wird kreisförmig sich ausbreitende Wellen erzeugen.

- Nun fängt man an, sich geradeaus in eine Richtung zu bewegen.

- Angenommen, man fliege dabei mit dem Kopf nach vorne, aber sehr langsam.

- Die Wellenteile, die sich von einem wegbewegen erscheinen jetzt langsamer.

- Die Wellenteile, die Richtung Füße laufen erscheinen aber schneller.

- Relativ zum Wasser bewegen sich die Wellenteile aber genauso schnell wie vorher.

- Nun kann man gedanklich auch schneller fliegen, als sich die Wellen fortbewegen.

- Das alles ist mit echten Wasserwellen so wie gedacht auch wirklich möglich.

- Das Wasser ist in diesem Modell sozusagen der Äther.

- Man kann den Gedanken dann übertragen auf Licht.

Hat man eine langsam strömende glatte Wasseroberfläche zur Verfügung, etwa in einem ruhig fließenden Fluss oder Priel, kann man mit Hilfe einer Filmkamera und einer Messlatte den Effekt des Äther anschaulich machen.

Von einem Stein im Wasser erzeugte Wellen pflanzen sich im Wasser immer mit derselben Geschwindigkeit fort. Die Geschwindigkeit des Steins in Richtung der Wellenbewegung spielt für die Geschwindigkeit der Wellen keine Rolle.

Wesentlich für das Verständnis der Äthertheorie ist, dass sich die Wellen in ihrem Medium immer mit derselben Geschwindigkeit relativ zum Medium fortpflanzen.

Experimentum crucis: Michelson-Morley

- Schon im Jahr 1871 deuteten sich Schwierigkeiten beim experimentellen Nachweis des Äthers an [4].

- Zwei Wissenschaftler, Michelson und Morley, ersannen dann im Jahr 1887 [5] einen Versuch ähnlich zum "Wasser-Äther"-Gedanken.

- Bewegt man sich in dieselbe Richtung, in der sich eine Lichtwelle im Äther ausbreitet, dann müsste man selbst relativ zu dieser Lichtwelle langsamer erscheinen.

- Und umgekehrt: Bewegt man sich entgegen der Ausbreitung des Licht, müsste die Lichtwelle schneller erscheinen.

- Ein berühmter Versuch dazu brachte aber ein völlig unerwartetes Ergebnis:

- Egal in welche Richtung und wie schnell man sich bewegt:

- Die relative Geschwindigkeit zum Licht ist immer dieselbe.

- Es sind immer in etwa 300 Tausend Kilometer pro Sekunde.

- Man nennt das die Konstanz der Lichtgeschwindigkeit.

- Dieser Befund ist mit dem Äthermodell unvereinbar.

Alber Einstein zum Äther

Albert Einstein geht in der Einführung zu seiner speziellen Relativitätstheorie aus dem Jahr 1905 ausdrücklich auf das Problem des Lichtäthers ein. Er spricht über "mißlungene Versuche, eine Bewegung der Erde relativ zum 'Lichtmedium' zu konstatieren". [18]

ZITAT:

Albert Einstein, 1905: "Die Einführung eines 'Lichtäthers' wird sich insofern als überflüssig erweisen, als nach der zu entwickelnden Auffassung weder ein mit besonderen Eigenschaften ausgestatteter 'absolut ruhender Raum' eingeführt, noch einem Punkte des leeren Raumes, in welchem elektromagnetische Prozesse stattfinden, ein Geschwindigkeitsvektor zugeordnet wird." [18]

Albert Einstein, 1905: "Die Einführung eines 'Lichtäthers' wird sich insofern als überflüssig erweisen, als nach der zu entwickelnden Auffassung weder ein mit besonderen Eigenschaften ausgestatteter 'absolut ruhender Raum' eingeführt, noch einem Punkte des leeren Raumes, in welchem elektromagnetische Prozesse stattfinden, ein Geschwindigkeitsvektor zugeordnet wird." [18]

Einstein geht also nicht mehr von einem ruhenden Lichtäther aus und versucht darin eine konstante Lichtgeschwindigkeit unterzubringen. Einstein geht stattdessenn von einer konstanten Lichtgeschwindigkeit aus und zieht daraus Schlüsse auf die Eigenschaften von Raum und Zeit:

ZITAT:

"Wir wollen diese Vermutung (deren Inhalt im folgenden 'Prinzip der Relativität' genannt werden wird) zur Voraussetzung erheben und außerdem die mit ihm nur scheinbar unverträgliche Voraussetzung einführen, daß sich das Licht im leeren Raume stets mit einer bestimmten, vom Bewegungszustande des emittierenden Körpers unabhängigen Geschwindigkeit V fortpflanze." [18]

"Wir wollen diese Vermutung (deren Inhalt im folgenden 'Prinzip der Relativität' genannt werden wird) zur Voraussetzung erheben und außerdem die mit ihm nur scheinbar unverträgliche Voraussetzung einführen, daß sich das Licht im leeren Raume stets mit einer bestimmten, vom Bewegungszustande des emittierenden Körpers unabhängigen Geschwindigkeit V fortpflanze." [18]

Arnold Sommerfeld zum Äther

War nun mit Einstein der Äther endgültig abgeschafft? Eher nicht: In einem Buch aus dem Jahr 1921 behandelte der Physiker Arnold Sommerfeld (1868 bis 1951) unter anderm das Atommodell von Niels Bohr. Sommerfeld sieht sowohl die klassische wie auch die neue Quantenphysik Einsteins Relativiätstheorie als relevant an. Das folgende Zitat zeigt deutlich den Übergang vom klassischen, materiellen Denken hin zu einem stärker theoretischen und nicht mehr anschaulichen Denken.

ZITAT:

Arold Sommerfeld, 1921: "Neben das Atom, welches die Strahlung anregt, stellt sich dann der „Äther", welcher die Strahlung fortpflanzt. Man spricht zwar, heutzutage nicht gern vom Äther, seitdem ihm durch die elativitätstheorie seine materielle Existenz im älteren Sinne genommen ist. Wir wollen hier mit dem Worte Äther nichts anderes ausdrücken, als die Möglichkeit von Schwingungszuständen mit der Fortpflanzungsgeschwindigkeit c, wie sie sich uns in der Erfahrung überall darbieten und durch die elektrodynamisch-optische Theorie näher

Arold Sommerfeld, 1921: "Neben das Atom, welches die Strahlung anregt, stellt sich dann der „Äther", welcher die Strahlung fortpflanzt. Man spricht zwar, heutzutage nicht gern vom Äther, seitdem ihm durch die elativitätstheorie seine materielle Existenz im älteren Sinne genommen ist. Wir wollen hier mit dem Worte Äther nichts anderes ausdrücken, als die Möglichkeit von Schwingungszuständen mit der Fortpflanzungsgeschwindigkeit c, wie sie sich uns in der Erfahrung überall darbieten und durch die elektrodynamisch-optische Theorie näher

umschrieben werden. In diesem Sinne definieren wir den Äther als Oscillator." [46]

Wie sehr Sommerfeld noch die Nähe zum mechanistischen Denken mit Materie als Grundlage physikalischer Vorgänge, behalten möchte, zeigt das folgende Zitat. Sommerfeld muss erklären, wie der hypothetische Äther mit beliebigen Frequenzen schwingen kann, während doch reale, mechanische Oszillatoren, oft idealisiert als harmonische Oszillatoren (näherungsweise z. B. ein Pendel), immer nur eine ganz bestimmte Eigenfrequenz haben.

ZITAT:

Arnold Sommerfeld, 1921: "Von dem eingeführten harmonischen Oscillator unterscheidet sich aber der Oscillator „Äther" (abgesehen von der räumlichen Anordnung und der raumzeitlichen Ausbreitung seiner Schwingungen, worauf es hier nicht ankommt) wesentlich dadurch, daß er jeder Schwingungszahl v fähig ist, das heißt, daß er von sich aus in jeder Farbe strahlen kann. Der Äther stellt also nicht einen Oscillator, sondern ein unendliches System von Oscillatoren dar, in dem die Eigenschwingungszahl kontinuierlich von Oscillator zu Oscillator variiert, sozusagen ein System von Orgelpfeifen mit unendlich kleinen Abstufungen der Tonhöhe." [46]

Arnold Sommerfeld, 1921: "Von dem eingeführten harmonischen Oscillator unterscheidet sich aber der Oscillator „Äther" (abgesehen von der räumlichen Anordnung und der raumzeitlichen Ausbreitung seiner Schwingungen, worauf es hier nicht ankommt) wesentlich dadurch, daß er jeder Schwingungszahl v fähig ist, das heißt, daß er von sich aus in jeder Farbe strahlen kann. Der Äther stellt also nicht einen Oscillator, sondern ein unendliches System von Oscillatoren dar, in dem die Eigenschwingungszahl kontinuierlich von Oscillator zu Oscillator variiert, sozusagen ein System von Orgelpfeifen mit unendlich kleinen Abstufungen der Tonhöhe." [46]

Das ganze mutet an wie ein Budenzauber, wie Doppeldenk, einem gleichzeitigen festhalten an mehreren widersprüchlichen Behauptungen. Es soll hier also mit Oszillatoren gedacht werden, sie haben aber keine Masse und keine Eigenfrequenz. Dafür gibt es unendlich viele von ihnen. Für den gesunden Menschenverstand der nach Anschaulichkeit fragt ist das eine Zumutung. Sommerfeld war sich der Spannung zwischen der alten mechanisch gedachten Welt und den sich nun auftuenden anti-anschaulichen Idee sicherlich bewusst.

Eine fixe Idee?

Als fix bezeichnet man Ideen, an denen Menschen auch entgegen guter Gründe starr festhalten wollen. Im Rückblick mag vielen die Idee eines Lichtäthers als solch eine fixe Idee erscheinen. Lehr- und Schulbücher behandeln sie meist nur als historisch interessant, hat doch Albert Einstein gezeigt, wie man ganz auf eine solche Vorstellung verzichten kann. Und auch die Idee eines Stoffes, der den Raum ausfüllt, ohne von Materie dabei verdrängt zu werden mag heute sonderbar bis befremdlich klingen. Aber ist die von Astronomen und Kosmologen heute angenommene Dunkle Materie denn nicht ähnlich vorstellbar? So wie man im 19ten Jahrhundert nach einem Medium zur Übertragung von Schwingungen suchte, so suchen wir heute nach einer materiellen Ursache für vermeintlich vorhandene Anziehungskräfte im Weltraum. Und ähnlich erfolglos wie die Wissenschaft im 19ten Jahrhundert versuchte den Äther nachzuweisen, so erfolglos sind wir heute im Nachweis der Dunklen Materie. Diese historische Parallele sollte uns bescheiden im Rückblick auf die geistigen Leistungen und das konsequente Denken in Modellen in der Zeit vor der Relativitätstheorie machen. Zum heutigen Problem, siehe den Artikel 👉 Dunkle Materie

Fußnoten

- [1] Lecture at Kings College (1862) as quoted by F. V. Jones, "The Man Who Paved the Way for Wireless," New Scientist (Nov 1, 1979) p. 348 & Andrey Vyshedskiy, On The Origin Of The Human Mind 2nd edition

- [2] Kapitel III. Der Äther (sehr umfangreich). In: Franz Serafin Exner: Vorlesungen über die physikalischen Grundlagen der Naturwissenschaften. Deuticke, Wien 1919, OBV.

- [3] Christiaan Huygens: Abhandlung über das Licht (= Ostwald’s Klassiker der exakten Wissenschaften. Nr. 20). 4. Auflage. Thun, 1996, ISBN 3-8171-3020-1 (französisch: Traité de la lumière. Leide 1690. Übersetzt von Rudolf Mewes, Verfasst um 1678, Nachdruck der Auflage von 1885).

- [4] George Biddell Airy: On the Supposed Alteration in the Amount of Astronomical Aberration of Light, Produced by the Passage of the Light through a Considerable Thickness of Refracting Medium. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 20 (130–138): 35–39. 1871.

- [5] Albert Abraham Michelson; Edward W. Morley: On the Relative Motion of the Earth and the Luminiferous Ether. American Journal of Science. 34 (203). 1887. pages 333–345.

- [6] Isaac Newton (1642 bis 1727) sieht unüberwindbare Probleme in der Idee eines Lichtäthers: "And it is as difficult to explain by these Hypotheses, how Rays can be alternately in Fits of easy Reflexion and easy Transmission; unless perhaps one might suppose that there are in all Space two Æthereal vibrating Mediums, and that the Vibrations of one of them constitute Light, and the Vibrations of the other are swifter, and as often as they overtake the Vibrations of the first, put them into those Fits. But how two Æthers can be diffused through all Space, one of which acts upon the other, and by consequence is re-acted upon, without retarding, shattering, dispersing and confounding one anothers Motions, is inconceivable. And against filling the Heavens with fluid Mediums, unless they be exceeding rare, a great Objection arises from the regular and very lasting Motions of the Planets and Comets in all manner of Courses through the Heavens. For thence it is manifest, that the Heavens are void of all sensible Resistance, and by consequence of all sensible Matter." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730).

- [7] Huygens nimmt eine materielle, mechanische Grundlage von Licht an: "It is inconceivable to doubt that light consists in the motion of some sort of matter. For whether one considers its production, one sees that here upon the Earth it is chiefly engendered by fire and flame which contain without doubt bodies that are in rapid motion, since they dissolve and melt many other bodies, even the most solid; or whether one considers its effects, one sees that when light is collected, as by concave mirrors, it has the property of burning as a fire does, that is to say it disunites the particles of bodies. This is assuredly the mark of motion, at least in the true Philosophy, in which one conceives the causes of all natural effects in terms of mechanical motions. This, in my opinion, we must necessarily do, or else renounce all hopes of ever comprehending anything in Physics." In: Treatise on light In which are explained the causes of that which occurs in reflexion, & in refraction and particularly in the strange refraction of Iceland crystal. Aus dem Französischen übersetzt von Silvanus P. Thompson. Französisches Original aus dem Jahr 1690: Traite de la Lumiere. Dort die Seite 3.

- [8] Huygens schließt umherfliegende Teilchen des Lichts aus, das sich Licht aus verschiedenen Richtungen selbst bei einer Überkreuzung nicht gegenseitig stört: "Further, when one considers the extreme speed with which light spreads on every side, and how, when it comes from different regions, even from those directly opposite, the rays traverse one another without hindrance, one may well understand that when we see a luminous object, it cannot be by any transport of matter coming to us from this object, in the way in which a shot or an arrow traverses the air; for assuredly that would too greatly impugn these two properties of light, especially the second of them. It is then in some other way that light spreads; and that which can lead us to comprehend it is the knowledge which we have of the spreading of Sound in the air." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 4. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690. Dort die Seiten 3 und 4.

- [9] Huygens sieht Licht in Analogie zum Schall in Luft: "We know that by means of the air, which is an invisible and impalpable body, Sound spreads around the spot where it has been produced, by a movement which is passed on successively from one part of the air to another; and that the spreading of this movement, taking place equally rapidly on all sides, ought to form spherical surfaces ever enlarging and which strike our ears. Now there is no doubt at all that light also comes from the luminous body to our eyes by some movement impressed on the matter which is between the two; since, as we have already seen, it cannot be by the transport of a body which passes from one to the other." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 4. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [10] Für den Träger des Lichts hat Huygens noch keinen Namen: "And as, according to this Philosophy, one holds as certain that the sensation of sight is excited only by the impression of some movement of a kind of matter which acts on the nerves at the back of our eyes, there is here yet one reason more for believing that light consists in a movement of the matter which exists between us and the luminous body." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 3. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [11] Das Licht breitete sich im Äther als Welle aus: "We know that by means of the air, which is an invisible and impalpable body, Sound spreads around the spot where it has been produced, by a movement which is passed on successively from one part of the air to another; and that the spreading of this movement, taking place equally rapidly on all sides, ought to form spherical surfaces ever enlarging and which strike our ears. Now there is no doubt at all that light also comes from the luminous body to our eyes by some movement impressed on the matter which is between the two; since, as we have already seen, it cannot be by the transport of a body which passes from one to the other. If, in addition, light takes time for its passage—which we are now going to examine—it will follow that this movement, impressed on the intervening matter, is successive; and consequently it spreads, as Sound does, by spherical surfaces and waves: for I call them waves from their resemblance to those which are seen to be formed in water when a stone is thrown into it, and which present a successive spreading as circles, though these arise from another cause, and are only in a flat surface." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 4. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [12] Huygens verwendet dann den Begriff des Äthers, im französischen Original spricht er von "particules éthérées" (Seite 17) oder "particules de l’éther " (Seite 18) sowie auch nur noch kurz vom Äther an sich "par la fréquenté per- RE cussion des corpuscules qui frappent l’éther" (Seite 21). In: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [13] Luft kann nicht der gesucht Äther des Lichts sein: "Now if one examines what this matter may be in which the movement coming from the luminous body is propagated, which I call Ethereal matter, one will see that it is not the same that serves for the propagation of Sound. For one finds that the latter is really that which we feel and which we breathe, and which being removed from any place still leaves there the other kind of matter that serves to convey Light. This may be proved by shutting up a sounding body in a glass vessel from which the air is withdrawn by the machine which Mr. Boyle has given us, and with which he has performed so many beautiful experiments. But in doing this of which I speak, care must be taken to place the sounding body on cotton or on feathers, in such a way that it cannot communicate its tremors either to the glass vessel which encloses it, or to the machine; a precaution which has hitherto been neglected. For then after having exhausted all the air one hears no Sound from the metal, though it is struck." Und: "One sees here not only that our air, which does not penetrate through glass, is the matter by which Sound spreads; but also that it is not the same air but another kind of matter in which Light spreads; since if the air is [Pg 12]removed from the vessel the Light does not cease to traverse it as before." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 11. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690.

- [14] Der Äther durchdringt Materie: "And this last point is demonstrated even more clearly by the celebrated experiment of Torricelli, in which the tube of glass from which the quicksilver has withdrawn itself, remaining void of air, transmits Light just the same as when air is in it. For this proves that a matter different from air exists in this tube, and that this matter must have penetrated the glass or the quicksilver, either one or the other, though they are both impenetrable to the air. And when, in the same experiment, one makes the vacuum after putting a little water above the quicksilver, one concludes equally that the said matter passes through glass or water, or through both." In: TREATISE ON LIGHT In which are explained The causes of that which occurs In REFLEXION, & in REFRACTION And particularly In the strange REFRACTION OF ICELAND CRYSTAL. By CHRISTIAAN HUYGENS. Rendered into English By SILVANUS P. THOMPSON. Dort die Seite 12. Im Französischen Original: Traite de la Lumiere. 1690. Die Betrachtung von Huygens ist eingebettet in Spekulationen zum hypothetischen 👉 Lichtäther

- [15] E. T. Whittaker. A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity: from the Age of Descartes to the Close of the Nineteenth Century. Dublin University Press series. London; New York; Dublin: Longmans, Green; Hodges, Figgis. 1910.

- [16] Maxwell fordert einen Äther, in: James Clerk Maxwell: On a possible mode of detecting a motion of the solar system through luminiferous ether. Posthum veröffentlicht in: Proceedings of the Royal Society. 30. 188. Dort die Seiten 108 bis 110. Siehe auch 👉 Michelson-Morley-Experiment

- [17] Das Video zur Nachstellung des Äthers mit Hilfe von Wasserwellen entstand im Juli 2024 auf der Nordseeinsel Wangerooge. Das Video ist näher beschrieben auf: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/98/Ätherwind_(Wasserwellen-Modell).webm

- [18] Albert Einstein: Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. In: Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 17, 1905, S. 891–921. Online: https://myweb.rz.uni-augsburg.de/~eckern/adp/history/einstein-papers/1905_17_891-921.pdf

- [19] James Clerk Maxwell: On physical lines of force. Philosophical Magazine. 90: 11–23. (1861). doi:10.1080/14786431003659180.

- [20] Rowan Hamilton schreibt 1833 über Huygens Idee von Licht in einem Äther: "...Huygens, who compared the gradual propagation of light, not to the

- [21] Der Astrophysiker Arthur Stanley Eddington geht noch im Jahr 1927 von der Existenz eines Äthers aus und hält fest, dass er nicht durch Atome beeinflusst zu werden scheint: "Thirty years ago there was much debate over the question of aether-drag—whether the earth moving round the sun drags the aether with it. At that time the solidity of the atom was unquestioned, and it was difficult to believe that matter could push its way through the aether without disturbing it. It was surprising and perplexing to find as the result of experiments that no convection of the aether occurred. But we now realise that the aether can slip through the atoms as easily as through the solar system, and our expectation is all the other way." In: Arthur Stanley Eddington: The Nature of the Physical World. MacMillan, 1928 (Gifford Lectures). Dort "Chapter I The Downfall of Classical Physics". Seite 3.

- [22] H. Fizeau: Sur les hypothèses relatives à l'éther lumineux, et sur une expérience qui parait démontrer que le mouvement des corps change la vitesse avec laquelle la lumière se propage dans leur intérieur, C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Volume 33 (1851), pp. 349-355

- [23] Die Anekdote zur mechanistischen Vorstellungen von Dingen, in denen Licht schwingen müsste findet sich in: Richard Feynman: Feymnan-Vorlesungen über Physik. Band 2. Elektromagnetismus und Struktur der Materie. Oldenbourg Verlag. 2007. ISBN:978-3-486-58107-2. Dort im Kapitel "1.5 Was sind Felder wirklich", Seite 14. Siehe auch 👉 Feynman Lectures

- [24] 1925 fasst ein französischer Mathematiker die Situation zu Beginn des 19ten Jahrhunderts zusammen: "Bereits Leibniz, Young, Huyghens und andere hatten, um die Lichtphänomene oder die universelle Anziehungskraft oder die Erhaltung der Energie zu erklären, die Existenz eines kontinuierlichen, unwägbaren Mediums im gesamten Raum, des Äthers, erdacht. Aber es ist Fresnel, der diese Vorstellung durchsetzt, nicht ohne Kampf. Der streng geradlinige Strahl Newtons sollte also diesen Wellen weichen, die nur noch eine ungefähre Strahlung übrig lassen und so schwer zu erklären sind! Mit Schmerz opferte die klassische Wissenschaft zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts die Emissionstheorie. Man kennt die Kontroverse zwischen Poisson und Fresnel, das Experiment mit dem Schirm, dessen Schatten an den äußersten Rändern nicht schwarz ist, weil die Lichtwellen über die Konturen des Schirms schwappen und sehr leicht in das Innere seines Bildes eindringen. Poisson wollte nie zugeben, dass es an den Rändern Licht gab. Aber die Errungenschaften der Wellentheorie überwinden alle Widerstände: Es ist die Theorie der Interferenzen und ihre unzähligen Anwendungen, es ist die Messung der kolossalen Geschwindigkeit des Lichts durch das Vakuum und durch transparente Körper, es ist die Spektralanalyse, die uns die chemische Zusammensetzung der Sterne enthüllt, eines der Unerkennbaren von Auguste Comte." Im französischen Original: "Mais c'est Fresnel qui impose cette conception, non sans combat, d'ailleurs. Le rayon rigoureusement rectiligne de Newton allait donc céder la place à ces ondulations, qui ne laissent plus subsister qu'un à peu près de rayon, et si péniblement expliqué ! C'est avec douleur qu'au début du XIXe siècle la science classique sacrifia la théorie de l'émission. On connaît la controverse de Poisson et de Fresnel, l'expérience de l'écran, dont l'ombre n'est pas noire sur les bords extrêmes parce que les ondes lumineuses déferlent sur les contours de l'écran et pénètrent très légèrement à l'intérieur de son image. Jamais Poisson ne voulut avouer qu'il y avait de la lumière sur les bords. Mais les conquêtes de la théorie ondulatoire emportent toutes les résistances : c'est la théorie des interférences et ses applications innombrables, c'est la mesure de la colossale vitesse de la lumière à travers le vide et les corps transparents, c'est l'analyse spectrale nous révélant la composition chimique des étoiles, un des inconnaissables d'Auguste Comte. " In: Paul Painlevé: Les conceptions modernes de la matière et la science classique. Discours prononcé à Londres, le 15 novembre 1927 devant la « Royal Institution of Great Britain. Eine kurze Zusammenfassung des Vortrages wurde 1927 in Nature veröffentlicht: [News and Views]. Nature 120, 777–781 (1927). Für eine volle Textversion siehe auch 👉 Materie und klassische Physik (Vortrag)

- [25] Eine sehr detailreiche und durchdachte Darstellung der historischen Entwicklung der Äthertheorie findet sich in: Ernst Mach: Die Prinzipien der physikalischen Optik; historisch und erkenntnispsychologisch entwickelt. Verfasst im Jahr 1913. Posthum veröffentlicht im Jahr 1921. Online: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/items/8b67a63d-a09f-475d-be13-b55d77a22402

- [26] Sehr ausführlich werden verschiedene theoretisch nötige Eigenschaften des Äthers als Träger elastischer elektrischer und magnetischer Schwingungen diskutiert in: Joseph Larmor: Dynamical Theory of the Electric and Luminiferous. Medium. Part III. Relations with Material Media. 1897. Online: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/epdf/10.1098/rspl.1897.0036

- [27] Im Jahr 1901 formuliert Emil Wiechert ausdrücklich, die Idee des Äthers als weiter zielführend für die Elektrodynamik: "Die neuere, sich auf Maxwell stützende Elektrodynamik ist durch die Unterscheidung zwischen Aether und Materie im Innern der sinnlich wahrnehmbaren Körper in so weitem Maasse zu den Ansichtn der ältere Schule urückgekehrt, dass der einstige Gegensatz nicht mehr besteht. Die 'elektrischen Teilchen' der alten Theorien sind wiederum zu Recht gelangt; wir haben aber gelernt,die Vermittelung ihrer Wechselwirkungen durch das Zwischenmedium zu verfolgen." Und: "H. A. Lorentz war der erste, der den Unterschied zwischen Aether und Materie in der Maxwell'schen Theorie mit Erfolg verwertete, und er machte dabei von vorneherein auf die Annäherung an die älteren Theorien aufmerksam, welche sich dann einstellt." In: Wiechert, E. (1901), Elektrodynamische Elementargesetze. Ann. Phys., 309: 667-689. https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.19013090403

- [28] Franz Exner sieht die ursprüngliche Motivation zur Annahme eines Äthers in dem Wunsch, die Annahme einer Fernwirkung, einer actio in distans zu vermeiden: "Der Ausdruck Äther stammt von Newton, der eben um die Actio in distans zu vermeiden, die Annahme eines solchen Mediums für absolut erforderlich hielt, schon mit Rücksicht auf die allgemeiben ausbreitung der Gravitation." In: Franz Serafin Exner: Vorlesungen über die physikalischen Grundlagen der Naturwissenschaften. Deuticke, Wien 1919, OBV. Dort die 79. Vorlesung. Seite 591.

- [29] Der Druck des Lichts als Indiz für einen Lichtäther: "[...] es gibt eine Reihe von Erscheinungen, welche die Existenz eines den ganzen Raum erfüllenden Mediums mehr als wahrcheinlich machen. Eine solche haben wir schon im Strahlungsdruck des Lichts kennen gelernt. es ist schwer, diesen anders zu begreifen ls durch Übertragung von lebendiger Kraft [kinetische Energie] in irgend einer Form." In: Franz Serafin Exner: Vorlesungen über die physikalischen Grundlagen der Naturwissenschaften. Deuticke, Wien 1919, OBV. Dort die 79. Vorlesung. Seite 592.

- [30] Die Rotverschiebung der Astronomie als Indiz für einen Lichtäther: "[...] neuere Untersuchungen haben die interessante Tatsache gelehrt, daß der Weltraum eine gewissermaßen selektive Absorption ausübt, d. h. nicht alle Strahlen in gleichem Maße schwächt. Wie es im großen und ganzen bei allen Materialien der Fall ist, so werden auch im Weltraum die kurzwelligen Lichtstrahlen stärker zurückgehalten als die langwelligen. Es zeigte sich, daß die Sterne um so röter sind, je größer ihre Entfernung ist und das bestätigt sich bis hin zu den weitesten Sternen, jenen der Milchstraße, an denen keine nachweisbare Parallaxe mehr zu bemerken ist. Ob dieses Überwiegen der roten Strahlen in dem Komplex, der uns ereicht, wirklich auf eine Absorption der kurzen Wellen im Weltraume zurückzuführen ist oder vielleicht auf eine Art diffuser Zerstreuung, ähnlich wie in trüben Medien, das bleibt dahingestellt; in beiden Fällen aber müßte ein wirksames Medium vorhanden sein. Direkt wurde in neuester Zeit dieser Effekt auch durch photographie Aufnahmen von Sternspektren nachgewiesen, wobei sich für die entfernteren Sterne das Spektrum am violetten Ende verkürzt zeigte." Exner machte diese Betrachtung im Zusammenhang mit einem hypothetischen Lichtäther. Er schränkt diesbezüglich ein: "Damit ist freilich die Existenz eines Äthers keineswegs erwiesen, denn das gleich würde durch irgendwelche fein verteilte Staubmassen im Raume auch hervorgebracht werden." In: Franz Serafin Exner: Vorlesungen über die physikalischen Grundlagen der Naturwissenschaften. Deuticke, Wien 1919, OBV. Dort in der 79. Vorlesung, Seite 592. Siehe auch 👉 Rotverschiebung

- [31] Es gäbe, so Exner 1919 "noch andere Erscheinungen, die wir ohne die Annahme eines Äthers schlechterdings nicht verstehen können." Nämlich: "[...] die Erscheinung der Aberration des Lichtes, das von den Fixsternen zu uns gelangt [...]. Dieselbe beweist auch, daß der Äther nicht an der Bewegung der Erde teilnimmt." In: Franz Serafin Exner: Vorlesungen über die physikalischen Grundlagen der Naturwissenschaften. Deuticke, Wien 1919, OBV. Dort in der 79. Vorlesung, Seite 592. Siehe auch 👉 Aberration

- [32] Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1886): De l'influence du mouvement de la terre sur les phénomènes lumineux. Archives Néerlandaises des Sciences Exactes et Naturelles, 21: 103–176.

- [33] Whittaker, Edmund Taylor (1910), A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity (1. ed.), Dublin: Longman, Green and Co.

- [34] Arago, A. (1810–1853), "Mémoire sur la vitesse de la lumière, lu à la prémière classe de l'Institut, le 10 décembre 1810", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, 36: 38–49

- [35] Fresnel, A. (1818), "Lettre de M. Fresnel à M. Arago sur l'influence du mouvement terrestre dans quelques phénomènes d'optique", Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 9: 57–66 (Sep. 1818), 286–7 (Nov. 1818);

- [36] Stokes, George Gabriel (1845), "On the Aberration of Light" , Philosophical Magazine, 27 (177): 9–15. DOI: doi:10.1080/14786444508645215

- [37] Stokes, George Gabriel (1846), "On the Constitution of the Luminiferous Æther, viewed with reference to the phænomenon of the Aberration of Light" , Philosophical Magazine, 29 (191): 6–10, doi:10.1080/14786444608562589

- [38] Lodge, Oliver J. (1897), "Experiments on the Absence of Mechanical Connexion between Ether and Matter" , Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 189: 149–166, Bibcode:1897RSPTA.189..149L, doi:10.1098/rsta.1897.0006

- [39] Wien, Wilhelm (1898), "Über die Fragen, welche die translatorische Bewegung des Lichtäthers betreffen (Referat für die 70. Versammlung deutsche Naturforscher und Aerzte in Düsseldorf, 1898)" , Annalen der Physik, 301 (3): I–XVIII.

- [40] Lorentz, H.A. (1899), "Stoke's Theory of Aberration in the Supposition of a Variable Density of the Aether", Proceedings of the Royal Society, 1: 443–448, Bibcode:1898KNAB....1..443L, archived from the original on 2008-04-04

- [41] Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1904), "Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity smaller than that of light" , Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 6: 809–831

- [42] Laue, Max von (1907), "Die Mitführung des Lichtes durch bewegte Körper nach dem Relativitätsprinzip" [The Entrainment of Light by Moving Bodies in Accordance with the Principle of Relativity], Annalen der Physik (in German), 23 (10): 989–990, Bibcode:1907AnP...328..989L, doi:10.1002/andp.19073281015

- [43] Miller, Dayton C. (July 1933). "The Ether- experiment and the determination of the absolute motion of the Earth". Reviews of Modern Physics. 5 (3): 203–254. Bibcode:1933RvMP....5..203M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.5.203. S2CID 4119615.

- [44] Hendrik Antoon Lorenzt, 1895, stellte nicht den Äther an sich in Frage Er frug nur, ob der Äther unbeweglich sei oder an der bewegten Materie hänge: "Die Frage, ob der Aether an der Bewegung ponderabler Körper theilnehme oder nicht, hat noch immer keine alle Physiker befriedigende Beantwortung gefunden. Für die Entscheidung können in erster Linie die Aberration des Lichtes und die damit zusammenhängenden Erscheinungen herangezogen werden, doch hat sich bis jetzt keine der beiden streitigen Theorieen, weder die von Fresnel, noch die von Stokes, allen Beobachtungen gegenüber voll und ganz bewährt, und so kann man bei der Wahl zwischen beiden Ansichten nur davon ausgehen, dass man die hüben und drüben noch verbleibenden Schwierigkeiten gegen einander abwägt. Auf diese Weise wurde ich schon vor längerer Zeit zu der Meinung geführt, dass man mit der Auffassung Fresnel’s, also mit der Annahme eines unbeweglichen Aethers, auf dem richtigen Wege sei. Zwar lässt sich gegen die Ansicht des Herrn Stokes kaum mehr als das eine Bedenken erheben, dass seine Voraussetzungen über die in der Nähe der Erde stattfindende Aetherbewegung sich widersprechen, aber dieses Bedenken fällt schwer ins Gewicht und ich sehe gar nicht, wie dasselbe zu beseitigen wäre. Der Fresnel’schen Theorie erwachsen Schwierigkeiten durch den bekannten Interferenzversuch des Hrn. Michelson und, wie Einige meinen, auch durch die Experimente, mittelst welcher Hr. Des Coudres einen Einfluss der Erdbewegung auf die Induction zweier Stromkreise vergebens nachzuweisen suchte". In: Hendrik Antoon Lorentz: Versuch eine Theorie der electrischen und optischen Erscheinungen in bewegten Körpern. Leiden. 1895.

- [45] Hendrik Antoon Lorentz versuchte bewusst, keine Annahmen über Gase oder Flüssigkeit auf den Äther zu übertragen: "Es liegt nicht in meiner Absicht [...] Vermuthungen über die Natur des Aethers auszusprechen. Ich wünsche nur, mich von vorgefassten Meinungen über diesen Stoff möglichst frei zu halten und demselben z. B. keine von den Eigenschaften der gewöhnlichen Flüssigkeiten und Gase zuzuschreiben. Sollte es sich ergeben, dass eine Darstellung der Erscheinungen am besten unter der Voraussetzung absoluter Durchdringlichkeit gelänge, dann müsste man sich zu einer solchen Annahme einstweilen schon verstehen und es der weiteren Forschung überlassen, uns, womöglich, ein tieferes Verständniss zu erschliessen." In: Hendrik Antoon Lorentz: Versuch eine Theorie der electrischen und optischen Erscheinungen in bewegten Körpern. Leiden. 1895.

- [46] Für den Physiker Ludwig Boltzmann war die Annahme eines Lichtäthers auf Grundlage von kleinen Teilchen von Materie ein klassiches Beispiel für den Versuch, in der Welt hinter den Erscheinungen eine tiefere Realität zu suchen. Über die vor allem französischen Wissenschaftler umd die Zeit der französischen Revolution schrieb er: "So dachte man sich die Materie, den zur Erklärung der Lichterscheinungen notwendigen Lichtäther und die beiden elektrischen Fluida als Summen mathematischer Punkte. Zwischen je zwei solchen Punkten dachte man sich eine Kraft wirksam, deren Richtung in ihre Verbindungslinie fällt und deren Intensität eine noch zu bestimmende Funktion ihrer Entfernung sein sollte". Wer Freude daran hat, Probleme nachzuempfinden, der beiße sich in dieses Bild hinein: man stelle sich eine Fläche vor auf der Kugeln liegen. Diese Kugeln sind mit elastischen Gummifäden verbunden. Die Gummifäden sollen eine Federkonstante haben (Kraft ist proportional der Dehnung). Nun überlege man sich selbst einmal wie man die Kraft auf jede einzelne Kugel berechnet, wenn man irgendeine der Kugeln aus ihrer momentanten Ruhelage entferne. Und man überlege dann weiter, wie man rechnerisch zu den Kräften gelangen kann, die auf jede Kugeln wirken, wenn man dieses Netz aus Kugeln im Weltraum einmal in Schwingung versetzt hätte. Das Zitat stammt aus: Boltzmann, Ludwig. "Über die Entwicklung der Methoden der theoretischen Physik in neuerer Zeit". Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung 8 (1900): 71-95.

- [46] Arnold Sommerfeld: Atombau und Spektrallinien. Verlag F. Vieweg & Sohn. Braunschweig. 1921. Dort auf Seite 245.