Korpuskeltheorie

Physik

© 2016

- 2025

Basiswissen|

Isaac Newton und die Korpuskulartheorie|

Konnte sich Newtons Theorie durchesetzen?|

Wie sieht man Licht heute?|

Fußnoten

Basiswissen

In der Physik steht das Wort Korpuskeltheorie[1] oder Korpuskulartheorie[2], auch Emissions-[3] oder Emanationstheorie[4], für die Annahme des Physikers Isaac Newton (1642 bis 1727), dass Licht aus materieartigen Bausteinen besteht. Im 19ten Jahrhundert wurde die Theorie zugunsten der Wellentheorie (Undulationstheorie) des Lichts verworfen. Das wird hier kurz vorgestellt.

Isaac Newton und die Korpuskulartheorie

Verschiedene Lexika[1][2] schreiben Isaac Newton (1642 bis 1727) die Idee zu, dass Licht aus kleinsten Körperchen, den Korpsukeln besteht. Tatsächlich kommt das englische Wort corpuscle insgesamt 15 mal in Newtons Opticks vor, wird dort aber stets nur im Sinne von farbgebenden Stoffen[5] verwendet. Heute würde man eher von Pigmenten sprechen. Seine hypothetischen Lichtteilchen hingegen bezeichnete Newton als "rays"[6], "bodies"[9] oder "simple Particles"[19]. Newton argumentierte unter anderem damit, dass sich Licht geradlinig ausbreite, was gut zu Teilchen passe, aber nicht etwa zu Druckphänomenen[10]. Wo Licht durch Materie in seiner Bahn abgelenkt werde, erklärt er das detailliert als Wirkung einer gravitativen Anziehungskraft[9]. Wo Newton Licht in Verbindung mit Wellenphänomen sah, war es das Medium, in dem Licht sich bewegte, welches sich wellenartig (vibrations) verhielt[9], nicht aber das Licht selbst. So versuchte er zum Beispiel auch das rätselhafte Phänomen der teilweisen (partiellen) Reflexion von Licht an Glasscheiben zu erklären[20]. Dass Licht aber ein Medium benötige, um sich ausbreiten - und damit auch einen Lichtäther - lehnte Newton ab[11].

Konnte sich Newtons Theorie durchesetzen?

Nein, Newtons Vorstellung von Licht als materieartigen Teilchen stand schon früh in Konkurrenz zur Idee von Licht als einer Wellen[12][13]. Experimente im frühen 19ten Jahrhundert konnten dann eindeutig den Wellencharakter des Lichts nachweisen[14]. Die Wellentheorie bezeichnete man später auch als => Undulationstheorie[15] ↗

Wie sieht man Licht heute?

Moderne Vorstellungen des Lichts verbinden weiterhin Teilchen- und Welleneigenschaften von den kleinstens Einheiten des Lichts. Man bezeichnet solche Teilchen heute als Lichtquant oder kurz auch als Photon ↗

Fußnoten

- [1] 1923, Newton Idee von Licht aus Korpuskeln: "Der große Newton hielt die Lichtstrahlen für Körperchen und sein Ansehen hat die Korpuskular-Theorie bis auf Eulers Zeit gehalten." In: Mauthner, Fritz: Wörterbuch der Philosophie. Leipzig 2 1923, Band 3, S. 436-497. Online: http://www.zeno.org/nid/2000618183X

- [2] 1908: Newtons Theorie des Lichts und ihre Grenzen: "Nach der älteren, besonders durch Newton (Optik vom Jahr 1698) vertretenen Hypothese, der Emissionstheorie (Emanationstheorie, Korpuskulartheorie) werden von den leuchtenden Körpern kleine Partikel eines Lichtstoffes ausgeworfen, die alle mit gleicher, in demselben Mittel konstanter Geschwindigkeit den Raum durcheilen, im Auge die Lichtempfindung erregen, an der Oberfläche und im Innern der Körper die mannigfaltigsten optischen Wirkungen erleiden und erzeugen. Die Hypothese ist gescheitert an ihrer Unfähigkeit, die Verminderung der Fortpflanzungsgeschwindigkeit des Lichts beim Uebergang von den optisch dünneren in die optisch dichteren Mittel, ferner die Erscheinungen der Polarisation und der Doppelbrechung und besonders die Erscheinungen der Interferenz zu erklären." In: Lueger, Otto: Lexikon der gesamten Technik und ihrer Hilfswissenschaften, Bd. 6 Stuttgart, Leipzig 1908., S. 151-158. Online: http://www.zeno.org/nid/20006076440

- [3] 1907 "Nach Thomson soll auch das Licht nichts anderes als ein Bombardement fliegender Korpuskeln sein (Newtons Emissions-Theorie). Vgl. Ionen." In: Kirchner, Friedrich / Michaëlis, Carl: Wörterbuch der Philosophischen Grundbegriffe. Leipzig 1907, S. 310-311. Online: http://www.zeno.org/nid/20003585018

- [4] 1836, als Emanationstheorie: "Die Emanation (Ausströmung) des L., das in seiner unwägbaren Substanz durchaus durch die Schwerkraft (Gravitation) nicht verändert oder gehemmt wird, übersteigt in ihrer Schnelligkeit jede Vorstellung." Sowie: "Newton's Emanationstheorie, die lehrt, daß das Licht von leuchtenden und erleuchteten Körpern ausströme, und Euler's Vibrationssystem, welches das Licht als einen stets zitternden, durch das Weltall verbreiteten Aether voraussetzt, vereinigen sich neuerdings erst in Schottin's Aethertheorie oder der Lehre vom Magneto-elektro-Chemismus." In: Damen Conversations Lexikon, Band 6. [o.O.] 1836, S. 347-349. Online: http://www.zeno.org/nid/20001746286

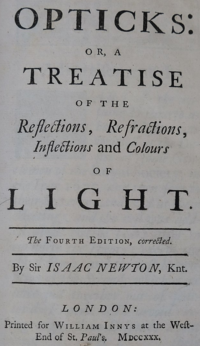

- [5] In seinem berühmten Buch Opticks verwendete Isaac Newton das Wort Korpuskel nicht im Sinne eines Lichtteilchens sondern eher in der Bedeutung dessen, was man heute als Farbpigment bezeichnen würde: "Between the parts of opake and colour'd Bodies are many Spaces, either empty, or replenish'd with Mediums of other Densities; as Water between the tinging Corpuscles wherewith any Liquor is impregnated, Air between the aqueous Globules that constitute Clouds or Mists; and for the most part Spaces void of both Air and Water, but yet perhaps not wholly void of all Substance, between the parts of hard Bodies." Sowie: "Nor is it much less to my purpose, that, by mixing divers Liquors, very odd and remarkable Productions and Changes of Colours may be effected, of which no cause can be more obvious and rational than that the saline Corpuscles of one Liquor do variously act upon or unite with the tinging Corpuscles of another, so as to make them swell, or shrink, (whereby not only their bulk but their density also may be changed,) or to divide them into smaller Corpuscles, (whereby a colour'd Liquor may become transparent,) or to make many of them associate into one cluster, whereby two transparent Liquors may compose a colour'd one." Oder: "For since it is of the Nature of Acids to dissolve or attenuate, and of Alcalies to precipitate or incrassate, if the Purple Colour of the Syrup was of the second Order, an acid Liquor by attenuating its tinging Corpuscles would change it to a red of the first Order, and an Alcali by incrassating them would change it to a green of the second Order." Das Wort "corpuscle" kommt in Newtons Opticks insgesamt 15 mal vor. Oft kommt es zusammen mit dem Wort tinging vor, was so viel wie farbgebend heißt. In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The_FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730).

- [6] Newton sprach von Licht auch als Strahlen (rays): "A transparent Body which looks of any Colour by transmitted Light, may also look of the same Colour by reflected Light, the Light of that Colour being reflected by the farther Surface of the Body, or by the Air beyond it. And then the reflected Colour will be diminished, and perhaps cease, by making the Body very thick, and pitching it on the backside to diminish the Reflexion of its farther Surface, so that the Light reflected from the tinging Particles may predominate. In such Cases, the Colour of the reflected Light will be apt to vary from that of the Light transmitted. But whence it is that tinged Bodies and Liquors reflect some sort of Rays, and intromit or transmit other sorts, shall be said in the next Book. In this Proposition I content my self to have put it past dispute, that Bodies have such Properties, and thence appear colour'd." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730). Siehe auch Lichtstrahl ↗

- [7] Newton sieht eine enge Verbindung von Wellenlängen zur Wahrnehmung von Farben: violett hat kleine, rot hat eine große Wellenlänge: "Do not several sorts of Rays make Vibrations of several bignesses, which according to their bignesses excite Sensations of several Colours, much after the manner that the Vibrations of the Air, according to their several bignesses excite Sensations of several Sounds? And particularly do not the most refrangible Rays excite the shortest Vibrations for making a Sensation of deep violet, the least refrangible the largest for making a Sensation of deep red, and the several intermediate sorts of Rays, Vibrations of several intermediate bignesses to make Sensations of the several intermediate Colours?" In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The_FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730). Siehe auch Farbwahrnehmung ↗

- [8] Newton erwog Licht in Verbindung mit Wellenphänomenen: "If a stone be thrown into stagnating Water, the Waves excited thereby continue some time to arise in the place where the Stone fell into the Water, and are propagated from thence in concentrick Circles upon the Surface of the Water to great distances. And the Vibrations or Tremors excited in the Air by percussion, continue a little time to move from the place of percussion in concentrick Spheres to great distances. And in like manner, when a Ray of Light falls upon the Surface of any pellucid Body, and is there refracted or reflected, may not Waves of Vibrations, or Tremors, be thereby excited in the refracting or reflecting Medium at the point of Incidence, and continue to arise there, and to be propagated from thence as long as they continue to arise and be propagated, when they are excited in the bottom of the Eye by the Pressure or Motion of the Finger, or by the Light which comes from the Coal of Fire in the Experiments above-mention'd? and are not these Vibrations propagated from the point of Incidence to great distances? And do they not overtake the Rays of Light, and by overtaking them successively, do they not put them into the Fits of easy Reflexion and easy Transmission described above? For if the Rays endeavour to recede from the densest part of the Vibration, they may be alternately accelerated and retarded by the Vibrations overtaking them." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730). Siehe auch Lichtwelle ↗

- [9] Newton beschreibt Licht eindeutig als Teilchen (bodies): "Are not the Rays of Light very small Bodies emitted from shining Substances? For such Bodies will pass through uniform Mediums in right Lines without bending into the Shadow, which is the Nature of the Rays of Light. They will also be capable of several Properties, and be able to conserve their Properties unchanged in passing through several Mediums, which is another Condition of the Rays of Light. Pellucid Substances act upon the Rays of Light at a distance in refracting, reflecting, and inflecting them, and the Rays mutually agitate the Parts of those Substances at a distance for heating them; and this Action and Re-action at a distance very much resembles an attractive Force between Bodies. If Refraction be perform'd by Attraction of the Rays, the Sines of Incidence must be to the Sines of Refraction in a given Proportion, as we shew'd in our Principles of Philosophy: And this Rule is true by Experience. The Rays of Light in going out of Glass into a Vacuum, are bent towards the Glass; and if they fall too obliquely on the Vacuum, they are bent backwards into the Glass, and totally reflected; and this Reflexion cannot be ascribed to the Resistance of an absolute Vacuum, but must be caused by the Power of the Glass attracting the Rays at their going out of it into the Vacuum, and bringing them back. For if the farther Surface of the Glass be moisten'd with Water or clear Oil, or liquid and clear Honey, the Rays which would otherwise be reflected will go into the Water, Oil, or Honey; and therefore are not reflected before they arrive at the farther Surface of the Glass, and begin to go out of it. If they go out of it into the Water, Oil, or Honey, they go on, because the Attraction of the Glass is almost balanced and rendered ineffectual by the contrary Attraction of the Liquor. But if they go out of it into a Vacuum which has no Attraction to balance that of the Glass, the Attraction of the Glass either bends and refracts them, or brings them back and reflects them. And this is still more evident by laying together two Prisms of Glass, or two Object-glasses of very long Telescopes, the one plane, the other a little convex, and so compressing them that they do not fully touch, nor are too far asunder. For the Light which falls upon the farther Surface of the first Glass where the Interval between the Glasses is not above the ten hundred thousandth Part of an Inch, will go through that Surface, and through the Air or Vacuum between the Glasses, and enter into the second Glass, as was explain'd in the first, fourth, and eighth Observations of the first Part of the second Book. But, if the second Glass be taken away, the Light which goes out of the second Surface of the first Glass into the Air or Vacuum, will not go on forwards, but turns back into the first Glass, and is reflected; and therefore it is drawn back by the Power of the first Glass, there being nothing else to turn it back." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730).

- [10] Isaac Newton betrachtet die Ausbreitung von Licht im wesentlichen als geradlinig, ohne Beugungseffekte wie etwa bei Schall oder Wasserwellen: "Light consisted only in Pression propagated without actual Motion, it would not be able to agitate and heat the Bodies which refract and reflect it. If it consisted in Motion propagated to all distances in an instant, it would require an infinite force every moment, in every shining Particle, to generate that Motion. And if it consisted in Pression or Motion, propagated either in an instant or in time, it would bend into the Shadow. For Pression or Motion cannot be propagated in a Fluid in right Lines, beyond an Obstacle which stops part of the Motion, but will bend and spread every way into the quiescent Medium which lies beyond the Obstacle. Gravity tends downwards, but the Pressure of Water arising from Gravity tends every way with equal Force, and is propagated as readily, and with as much force sideways as downwards, and through crooked passages as through strait ones. The Waves on the Surface of stagnating Water, passing by the sides of a broad Obstacle which stops part of them, bend afterwards and dilate themselves gradually into the quiet Water behind the Obstacle. The Waves, Pulses or Vibrations of the Air, wherein Sounds consist, bend manifestly, though not so much as the Waves of Water. For a Bell or a Cannon may be heard beyond a Hill which intercepts the sight of the sounding Body, and Sounds are propagated as readily through crooked Pipes as through streight ones. But Light is never known to follow crooked Passages nor to bend into the Shadow. For the fix'd Stars by the Interposition of any of the Planets cease to be seen. And so do the Parts of the Sun by the Interposition of the Moon, Mercury or Venus. The Rays which pass very near to the edges of any Body, are bent a little by the action of the Body, as we shew'd above; but this bending is not towards but from the Shadow, and is perform'd only in the passage of the Ray by the Body, and at a very small distance from it. So soon as the Ray is past the Body, it goes right on." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730).

- [11] Isaac Newton (1642 bis 1727) sieht unüberwindbare Probleme in der Idee eines Lichtäthers: "And it is as difficult to explain by these Hypotheses, how Rays can be alternately in Fits of easy Reflexion and easy Transmission; unless perhaps one might suppose that there are in all Space two Æthereal vibrating Mediums, and that the Vibrations of one of them constitute Light, and the Vibrations of the other are swifter, and as often as they overtake the Vibrations of the first, put them into those Fits. But how two Æthers can be diffused through all Space, one of which acts upon the other, and by consequence is re-acted upon, without retarding, shattering, dispersing and confounding one anothers Motions, is inconceivable. And against filling the Heavens with fluid Mediums, unless they be exceeding rare, a great Objection arises from the regular and very lasting Motions of the Planets and Comets in all manner of Courses through the Heavens. For thence it is manifest, that the Heavens are void of all sensible Resistance, and by consequence of all sensible Matter." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730). Siehe auch Lichtäther ↗

- [12] Francesco Maria Grimaldi: Physicomathesis de lumine, coloribus, et iride, aliisque annexis, Bologna 1665. Siehe auch Francesco Maria Grimaldi ↗

- [13] Christiaan Huygens: Traité de la lumière, 1690 (Abhandlung über Reflexion und Refraktion, Wellentheorie des Lichts); deutsch: Abhandlung über das Licht. W. Engelmann, Leipzig 1890. Siehe auch Christiaan Huygens ↗

- [14] Thomas Young, Experimental Demonstration of the General Law of the Interference of Light, "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London", vol 94 (1804). URL: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rstl.1804.0001

- [15] In einem Lexikon aus dem Jahr 1838 heißt es: "Der erste Augenschein rechtfertigt die Annahme, daß das Licht von den leuchtenden Körper nach allen Seiten zu in geraden Linien ausgeht, und demgemäß ist die gewöhnliche Vorstellung und Redeweise vom Lichte so, als bestehe dasselbe in einem seinen Stoffe, welcher in unendlich vielen und unendlich dünnen Strahlen von den leuchtenden Körpern ausgesendet werde. Die einfachern Lichtphänomene lassen sich auch recht deutlich von dieser Vorstellungsweise aus erklären, und nur erst bei den zusammengesetzteren zeigt es sich, daß jene Vorstellung falsche Begriffe enthält. Von den beiden angegebenen, der Lehre vom Licht zu Grunde gelegten Vorstellungsweisen hat man die erste die Emanationstheorie (d.h. Ausflußlehre), die zweite die Vibrations- oder Undulationstheorie (d.h. Erzitterungs- oder Wellenlehre) genannt." In: Der Artikel Licht im Brockhaus Bilder-Conversations-Lexikon, Band 2. Leipzig 1838., S. 740-742. Online: http://www.zeno.org/nid/20000840858

- [16] Newton sieht auch Farben als Effekte unterschiedlich großer Lichtteile (rays of light): "Nothing more is requisite for producing all the variety of Colours, and degrees of Refrangibility, than that the Rays of Light be Bodies of different Sizes, the least of which may take violet the weakest and darkest of the Colours, and be more easily diverted by refracting Surfaces from the right Course; and the rest as they are bigger and bigger, may make the stronger and more lucid Colours, blue, green, yellow, and red, and be more and more difficultly diverted. In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730). Dort die Question 29. Siehe auch Farbwahrnehmung ↗

- [17] Newton lässt seine Lichtteilchen Wellen in ihrem Medium erzeugen, die dann wieder auf die Teilchen zurückwirken können: "Nothing more is requisite for putting the Rays of Light into Fits of easy Reflexion and easy Transmission, than that they be small Bodies which by their attractive Powers, or some other Force, stir up Vibrations in what they act upon, which Vibrations being swifter than the Rays, overtake them successively, and agitate them so as by turns to increase and decrease their Velocities, and thereby put them into those Fits. And lastly, the unusual Refraction of Island-Crystal looks very much as if it were perform'd by some kind of attractive virtue lodged in certain Sides both of the Rays, and of the Particles of the Crystal. For were it not for some kind of Disposition or Virtue lodged in some Sides of the Particles of the Crystal, and not in their other Sides, and which inclines and bends the Rays towards the Coast of unusual Refraction, the Rays which fall perpendicularly on the Crystal, would not be refracted towards that Coast rather than towards any other Coast, both at their Incidence and at their Emergence, so as to emerge perpendicularly by a contrary Situation of the Coast of unusual Refraction at the second Surface; the Crystal acting upon the Rays after they have pass'd through it, and are emerging into the Air; or, if you please, into a Vacuum. And since the Crystal by this Disposition or Virtue does not act upon the Rays, unless when one of their Sides of unusual Refraction looks towards that Coast, this argues a Virtue or Disposition in those Sides of the Rays, which answers to, and sympathizes with that Virtue or Disposition of the Crystal, as the Poles of two Magnets answer to one another. And as Magnetism may be intended and remitted, and is found only in the Magnet and in Iron: So this Virtue of refracting the perpendicular Rays is greater in Island-Crystal, less in Crystal of the Rock, and is not yet found in other Bodies. I do not say that this Virtue is magnetical: It seems to be of another kind. I only say, that whatever it be, it's difficult to conceive how the Rays of Light, unless they be Bodies, can have a permanent Virtue in two of their Sides which is not in their other Sides, and this without any regard to their Position to the Space or Medium through which they pass." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730). Dort die Question 29.

- [18] Richard Feynman Physics Lecture 01 - Photons, Corpuscles of Light. Douglas Robb Memorial Lecture. 1979. University of Auckland. New Zealand. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyssfKRsgMU&ab_channel=Sk%C3%A9pseis

- [19] Isaac Newton (1642 bis 1727) vermutet ausdrücklich, dass Licht aus denselben festen Teilchen (simple Particles) besteht wie auch feste und flüssige Körper: "All Bodies seem to be composed of hard Particles: For otherwise Fluids would not congeal; as Water, Oils, Vinegar, and Spirit or Oil of Vitriol do by freezing; Mercury by Fumes of Lead; Spirit of Nitre and Mercury, by dissolving the Mercury and evaporating the Flegm; Spirit of Wine and Spirit of Urine, by deflegming and mixing them; and Spirit of Urine and Spirit of Salt, by subliming them together to make Sal-armoniac. Even the Rays of Light seem to be hard Bodies; for otherwise they would not retain different Properties in their different Sides." In: Isaac Newton: OPTICKS: OR, A TREATISE OF THE Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and colours OF LIGHT. The FOURTH EDITION, corrected. By Sir ISAAC NEWTON, Knt. LONDON: Printed for WILLIAM INNYS at the West-End of St. Paul's. MDCCXXX (1730). Dort die Seite 389.

- [20] Wie geistreich aber letztendlich erfolglos Isaac Newton (1642 bis 1727) versucht hatte, die partielle Reflexion von Licht an Glasscheiben zu erklären schildert sehr ausführlich der Physiker und Nobelpreisträger Richard Feynman (1918 bis 1988). Trifft Licht auf eine Glasscheibe, so kann je nach Winkel und Beschaffenheit des Glases mehr oder weniger Licht reflektiert werden. Feynman schreibt von 4 % bis 16 % des einfallenden Lichtes. Angenommen es seie zu Beginn des Versuches nur 4 % die reflektiert werden und 96 % Licht die durch das Glas hindurchgehen. Wenn man dann die Glasscheibe zunehmend dicker macht, steigt damit einhergehend der Anteil des reflektierten Lichtes bis auf 16 % an. Bei einer weiteren Verdickung sinkt er dann wieder auf 4 % ab. Man könne diesen Zyklus, so Feynman, bis zu 100 Millionen Mal wiederholen. Feynman zufolge war Newton mit dem Phänomen vertraut und er versuchte es im Sinne seiner "Korpuskeln" so zu erklären, dass die Lichtteilchen beim Eindringen in das Glas dort eine "Welle oder Feld" erzeugen. Diese Welle schaffe dann, so Newton nach Feynman, die Voraussetzung, dass das Licht je nach Abhängigkeit der Glasdicke mehr oder minder stark reflektiert werden. Newton, so Feynman, habe von "Vorgängen leichter Reflexion oder leichter Durchlässigkeit" gesprochen. In: Richard Feynman: QED: Die seltsame Theorie des Lichts und der Materie. Piper Verlag. 1. Auflage 1992. ISBN: 3-492-21562-9. Dort die Fußnote auf den Seiten 33 und 34. Siehe auch partielle Reflexion ↗